Dissertaties Historische Kartografie / Theses History of Cartography

Piet Broeders

Von Derfelden van Hinderstein

Gijsbert Franco Baron von Derfelden van Hinderstein, 1783-1857: Leven en werk van ‘eene ware specialiteit’ in kaart gebracht

Diss. Utrecht 21 November 2011

Terug naar overzicht dissertaties / Back to overview PhD-theses

English Summary

Gijsbert Franco Baron von Derfelden van Hinderstein, 1783-1857: Mapping the life and work of ‘a true speciality’

Gijsbert Franco baron von Derfelden van Hinderstein is a rather unknown Dutch cartographer of the 19th century. Neither his life nor his maps have ever been examined. In the auction catalogue of his ibrary a biographical sketch can be found; for other information a researcher has to make use of several archives and libraries. In my investigation I have located all his maps, and studied them in the context of his biography and the 19th century history of water management in the Netherlands and Dutch colonial politics in the East Indies. My point of view is the ‘information streams’. I asked myself the following questions: why did Von Derfelden make these maps, who appointed him the task, from what persons and authorities did he receive the geo-information he needed, who were the people that used the maps?

Von Derfelden was born in Utrecht in 1783 and died there in 1857. His father, born in Estonia as a member of the German nobility, joined the army of the States of the Dutch United Provinces in 1759. His mother acquired the entailed inheritance of the prominent family De Milan Visconti, who owned some estates and a lot of farms and farming-land around Utrecht.

Von Derfelden lived in a society that was changing drastically: the old nobility was put aside; the Dutch cast India Company went bankrupt; new forms of government were established: first the Batavian Republic and a few years later – in 1806 – the Kingdom of Holland; then – in 1810 – Holland was annexed by France for some time; in 1814 the Low Countries became a Kingdom and a colonial Empire; and in 1830 Belgium seceded.

During this time there were major problems: the water and ice masses of the rivers Rhine-Lek, Waal and Maas threatened the northern provinces of the country. A central water management superseded the centuries old dike boards in some aspects.

Being a gentleman of independent means Von Derfelden lived at the estate ‘Snellenburg’ at Benschop (province of Utrecht) from 1809 till 1840, where he developed his cartographical capacities, which was not that strange, because even at an early age mathematics and geography had been his passion.

His capabilities he first put in service of the Hoogheemraadschap van de Lekdijk Benedendams [the conservancy board of the Lek dike below the dam] trying to express its old rights of sovereignty in the dike management, and afterwards of the Dutch Government concerning the visualisation of [assumed] Dutch sovereignty over the Indian Archipelago.

In his function of ‘Hoogheemraad van de Lekdijk Benedendams’ [Member of the aforesaid board] (1817-1828) he made maps of (the dike alongside) the river mentioned previously, between 1820 and 1830.

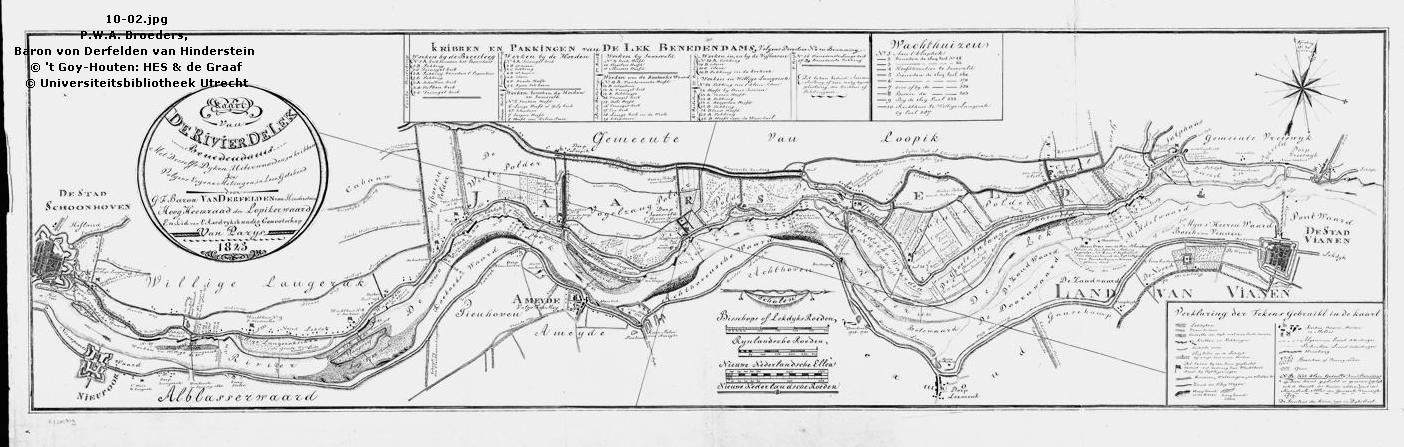

In the 13th century commissioned by the bishop of Utrecht and the count of Holland the board concentrated its attention on its own part of the dike between the little towns of Vianen and Schoonhoven. In the course of the 18th century Holland, Utrecht and Gelderland were trying to join forces in water management because of the yearly returning threat of high water and ice (that might damage the dikes,). Towards the end of that century a departement for the maintainance of dikes, roads, bridges, navigability of canals, etc. was formed. Centralizing the management caused tension in the above-mentioned board. Anyhow it wished to be accepted as a responsible and honorable institute. As the river map used by the board was out of date, Von Derfelden drew some new ones.

The first one (1821) was a manuscript of about 80 x 475 cm. with among other data the names of the adjacent land owners and tenant-farmers. The map was used by the board’s administration and dike management.

In 1823 Von Derfelden scaled down the map of 1821, leaving out a lot of information, in preparation of the lithographic one that was printed in 1824 in a hundred copies. This map can be considered a status symbol of the board: copies were sent to the King, the Ministries, the provincial government and adjacent boards.

The last one he drew was a manuscript of the dike (1829). By government order a committee had studied all the improvement plans of the dikes in the river areas. Those plans of hydraulic engineers and other experts were related to measures that were taken against the potential burst of the river-dikes of the Rhine-Lek, Waal, etc. which had really happened several times in the preceding decades. One of the most urgent things the said committee recommended was improving the Noorder Lekdijk [the dike at the north side of the Lek]. But the government cut down on the funds for the improvement project which meant that six parcels of the dike were left unconsolidated in 1827. Two years later the board requested the province to execute the original plans. The map with the different parcels and dike-profiles made by Von Derfelden supported the request.

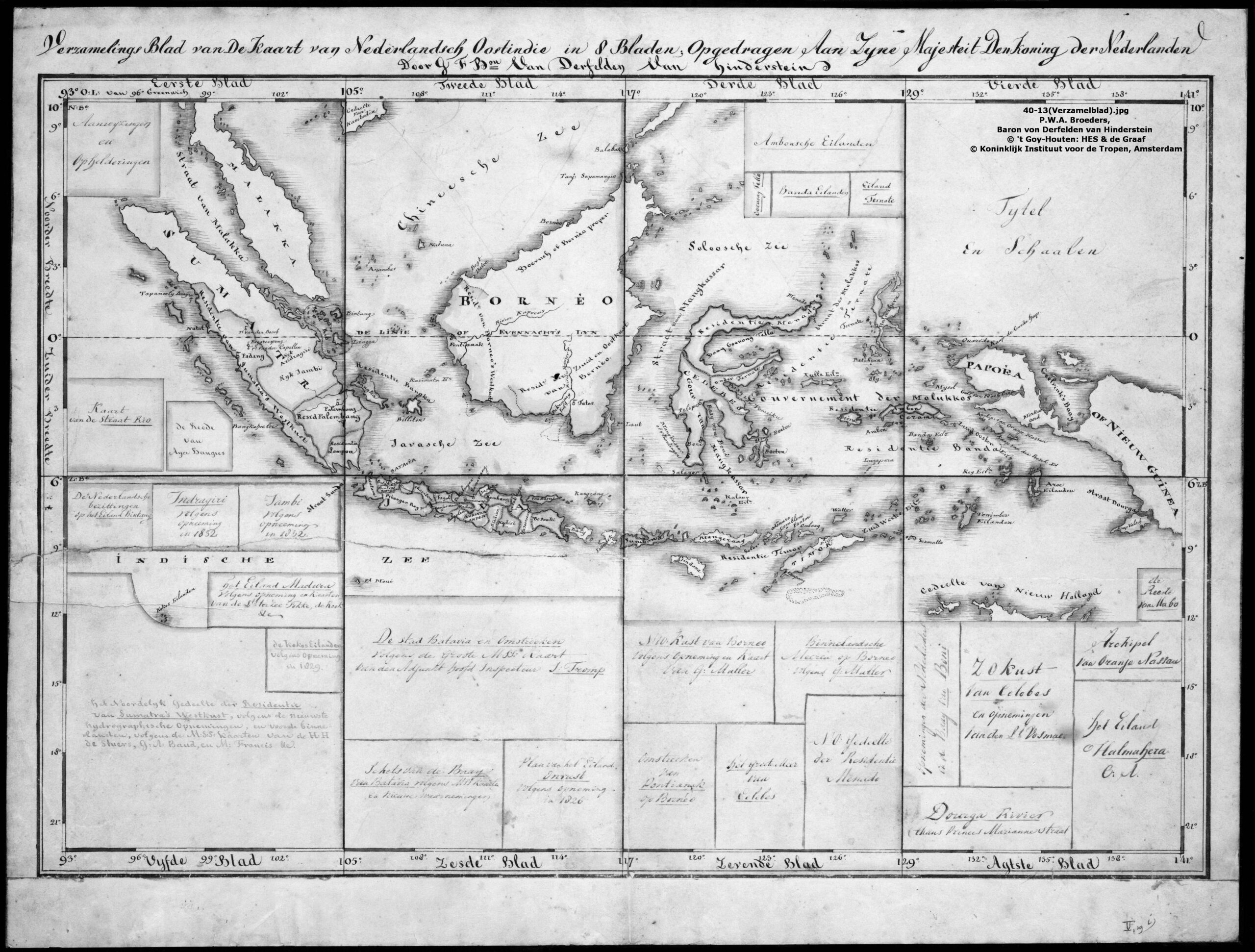

It took Von Derfelden some nine years, from 1828 till 1837 to draw an elaborate map of the Netherlands East Indies in eight sheets [160 x 240 cm.] and an index map.

In the year the negotiations for retrocession of the colonial areas commenced in London (1814) Von Derfelden began upon maps of the different islands of the Indian Archipelago. Between 1814 and about 1825 he made nine manuscripts of that area (under which head are also included the Philippines and New Holland).

Von Derfelden’s friend Van der Capellen was Governor-General of the East Indies between 1816 and 1826. Returned in patria, he stimulated Von Derfelden to compile all the available topographical information of the archipelago the Governor-General possessed. In 1828 Von Derfelden addressed the King with a petition requesting acceptance of the dedication to Him of eene geheele nieuwe en volledige grote kaart van Uwe Majesteits Oosterse Bezittingen’ [a total new and complete great Map of Your Majesty’s Eastern Possessions].

The aims Von Derfelden pursued in this map were the honour of the nation and of the Dutch cultivation and promotion of Geography, the support of the East Indian administration and safe navigation in respect of the waters in the Indian archipelago. Similarly he supported the government’s aims concerning the visualisation of Dutch sovereignty.

In 1828-1836 he made about 350 sketches, copies and other manuscripts of maps that had been placed at his disposal by Van der Capellen, the Department of the Colonies, officers of the Dutch Colonial Marine, employers of the East Indian government and French explorers. In the meantime he had bought all the printed English maps that he judged being important. In this way Von Derfelden scraped together all the relevant available East Indian topographical information of the periods of the French influence (1806-1811), of the British government (1811-1816/19) and of the developing of the Dutch colonial state until the year 1836.

After having made three versions, each time updating them in a larger scale, and doing that in conformity with the most recent geographical data, Von Derfelden submitted the manuscript to a committee of examination in 1836. The result was he had to renew the map image of Java. In 1837 by Royal Decree it was determined the map should be published at the expense of the Ministry of Colonies.

In 1838 the map was redrawn at the Department of War. Between 1839 and 1842 six engravers made the nine copperplates necessary for printing and between 1841 and 1843 all the sheets were printed in a thousand copies. In 1841 the first three sheets were for sale. In the same year the Memoire analytique was printed too. In this book Von Derfelden gave an account of his selection of all the available maps. Employing this method Von Derfelden was the first one to bring the Dutch colonial cartography on a scientific level.

The price of a set maps including the said book was 60 Dutch guilders. Because of the high price not many people were interested: towards the end of 1845 about 350 sets had been sold. In 1850 the price was reduced to 8 guilders a set. In the beginning of 1851 there were some 400 left. Since then their value was not much more than that of waste paper.

Three reasons can be given why the project went wrong: a very high price, bad publicity and the rise of a new generation of maps of the East Indies. The large wall map in its quality of a ‘status map’ was replaced by smaller ones each representing the separate islands.

At the outset the opinions of the map had been positive, but at the end of the fourties that changed because the maps of Melvill van Carnbee and other mapmakers had been brought up to date.

Based on studies of just one group of small islands the whole map received negative reviews: J.P. Veth discussed the Mantawei-islands [at the west-side of Sumatra] (1849) and H. von Rosenberg did so for a few islands west of New-Guinea (1862).

Although the project itself was not very successful, it influenced Dutch map publishers. In the mean time the interest people had for maps of the East Indies increased. Some publishers had engravers make cheap maps of the Indies. Most of these maps were old fashioned: the islands didn’t have the correct form and/or the topographical information given was hardly sufficient. One publisher plagiarized unpublished information from Von Derfelden’s map.

In the sixties of the 19th century Von Derfelden’s map got out of date.

Still during the 20th century Von Derfelden and his maps were considered matters of minor importance to the History of Cartography: only Koeman, Voskuil and Donkersloot-De Vrij paid a little attention to this cartographer. I happened to come across Von Derfelden’s name in 1990 when studying the garden of Snellenburg, the estate where Von derfelden lived from 1809 untill 1840. Afterwards, from 1100 onwards Dr. P. van den Brink of the University of Utrecht stimulated me to investigate life and works of Von Derfelden and Prof. dr. G. Schilder directed my attention to the Bonaparte collection in the Departement des Cartes et Plans of the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. In that collection there are the nearly 400 manuscripts of Von Derfelden’s collection of which the biggest part was drawn by himself. Prince Roland Bonaparte had bought this collection in 1891 in Amsterdam and left it to the Société de Géographie in Paris, when he died.

Von Derfelden was not only engaged in mapmaking, but also studied other aspects of geography. For years he corresponded with members of the Société de Géographie in Paris about different subjects, such as the borders between Europe and Asia, the sources of the Nile and the voyages of the American explorer Wilkes to Antarctica. Very interested in Japan, Von Derfelden probably should have undertaker. as well a new project to make maps of that archipelago if his wife had not died.

In his dissertation about Von Derfelden Prof. Koeman wrote: ‘ [He] was an active geographer. His work is little known and merits more attention than it has hitherto received.’ It afforded me much pleasure to have studied Von Derfelden and his maps, and I hope to have contributed not only to the reputation of this cartographer and the scientific method he employed in the process of publishing his maps, but also to the history of map making of both the great rivers in Holland and the Dutch East Indies in the early nineteenth century.